Few things are more luxurious in New York City than a weekend stretched before you void of commitments. The city is an alluring suitor who you’ve nonetheless chosen to scorn and ignore. Instead, you’re utterly free to revel in your own whims. It was a weekend like this when some instinct commanded me from my coffee shop, not to Washington Square Park or a museum, but to the darkness of my apartment with a very itchy idea.

It was the fall of 2016, and at the time, I’d had a religious custom of spending every Saturday and Sunday morning at my favorite coffee joint on Sullivan Street with my journal and The New York Times. The people who worked there knew me by name, order, and the sketches of vague personal facts from our exchanges. I enjoyed indulging in the fantasy that this made me special. I was a local, known and belonging to the circuitry of New York City and its caffeine guardians—at least on this particular street. Of course, in a city of millions, each of us with our own favorite java dispensaries, we’re not special at all. We’ve merely been persistent—merely managed to survive in a zip code long enough for the people there to learn our name. For every New Yorker who wasn’t born here, visiting our local coffee shop every morning feels like a small victory. As of yet, we haven’t gone back to wherever we came from with our tails between our legs. Mostly, making a life in New York isn’t even about “liking” it. It’s about not letting it defeat you. It was November of 2016, and by then, I’d been staving off defeat for thirteen years with my daily coffee amongst other locals like me—our small, frothy stakes in the ground. Our resistance. And it felt good. Maybe tomorrow, you’ll finally break me, but not today. This is my coffee shop.

I’d come to New York from Richmond, Virginia, when I was eighteen with a dream of becoming an artist one day. I imagined living in a cold loft with high ceilings and beautiful but cracked windows, painting soaring canvases by candlelight in my socks. Now, I was thirty-two and had indeed managed to make some art—a lot of it. But instead of a painter’s loft and big, romantic canvases, I’d mostly spent my postgrad years glued to a computer screen churning out graphic design jobs to make ends meet and feed the money machine its rent. It wasn’t where I hoped I’d be, but I was grateful and proud to be sliding into my second decade in New York on my own elbow grease.

Then November 8th hit. I remember walking to my coffee shop the morning after the U.S. general election—everyone looked red-eyed, like they’d either been up too late or had just suffered some kind of aneurysm to their soul. The external world suddenly felt more chaotic than ever, and our uncertain future ahead was a place I feared to imagine. I went inward. It was there—locked away in this interior plane—that the atoms of some distant idea began to percolate. As they bubbled and bounced around my skull, they started to become bothersome. “Out. Out,” they seemed to chant.

THe Making of

The Rosalyn Letters

Epilogue By S. Blake

Idea Atoms

Goulash

It was another Monday morning at my company’s TriBeCa office, and after some standard friendly banter about our weekends, I excitedly but timidly logged into my personal email account to show my coworkers the beginnings of a little side project I’d been chipping away at in my personal time. It was March of 2019, and I’d already logged more than two years molding it. The project was laid out in Google Slides, just like the hundreds of presentations and creative pitches I’d made over my decade and a half of working in advertising and product startups. The slides helped me move content around quickly and easily with the safety of a revision history to fall back on if I regretted a decision. However, this time I wasn’t pitching anything. This one was all for me. And it didn’t so much as resemble a pitch presentation as it did a puzzling mix between a coffee table art book, a website, a half-finished volume of gothic poetry, and a graphic novel. My colleagues were supportive—and even slightly humored—but I could tell they were also very confused. That’s probably because I was too.

About half a year earlier, I’d started making a more concerted effort to remove myself from “the grind” as much as possible. I reconnected with my love of poetry and performance art. I was reading a new book every few weeks. I was having more honest conversations with my friends about my creative curiosities, vulnerabilities, and process. And though I was still consistently and quietly making personal art, I’d noticed how I seemed to bore easily if my images lacked a storyline or expressed purpose. I spent more time connecting with my body through sports and the outdoors. I’d taken a retreat to Colombia to explore medicine healing and root myself in a more intuitive, nature-based understanding of the universe. I felt more ready to share with others the mysterious storytelling project I’d been working on for two years now in the late hours of nights and weekends. Conceptually, I knew exactly what I wanted to articulate. Executionally, I still had my work cut out. When the first words had demanded their freedom from their entrapment of my skull two years prior, I didn’t know much of anything—only an impulse to obey a few quiet instincts. Strangely, what had emerged was not some omniscient narration or description of a scene but inexplicably several lines of rhyming AABB poetry in the main character’s voice. Somehow I knew her name was Rosalyn.

I began to imagine what a written story might feel like if it was a closer cousin to The Who’s Tommy or David Bowie’s Ziggy Stardust than to a novel, their albums containing full story arcs from start to finish, complete with characters and scenes. Yet alone, each individual song still carries its own narrative and musical power in isolation. Could elements of a book do that too? I wondered what a graphic novel might look like if it was drawn by Miró, Hilma af Klint, or Basquiat instead of Dave Gibbons. And what might it sound like if it were read by Patti Smith? Questions like these made the work ahead exceptionally slow, messy, and circuitous but endlessly fascinating.

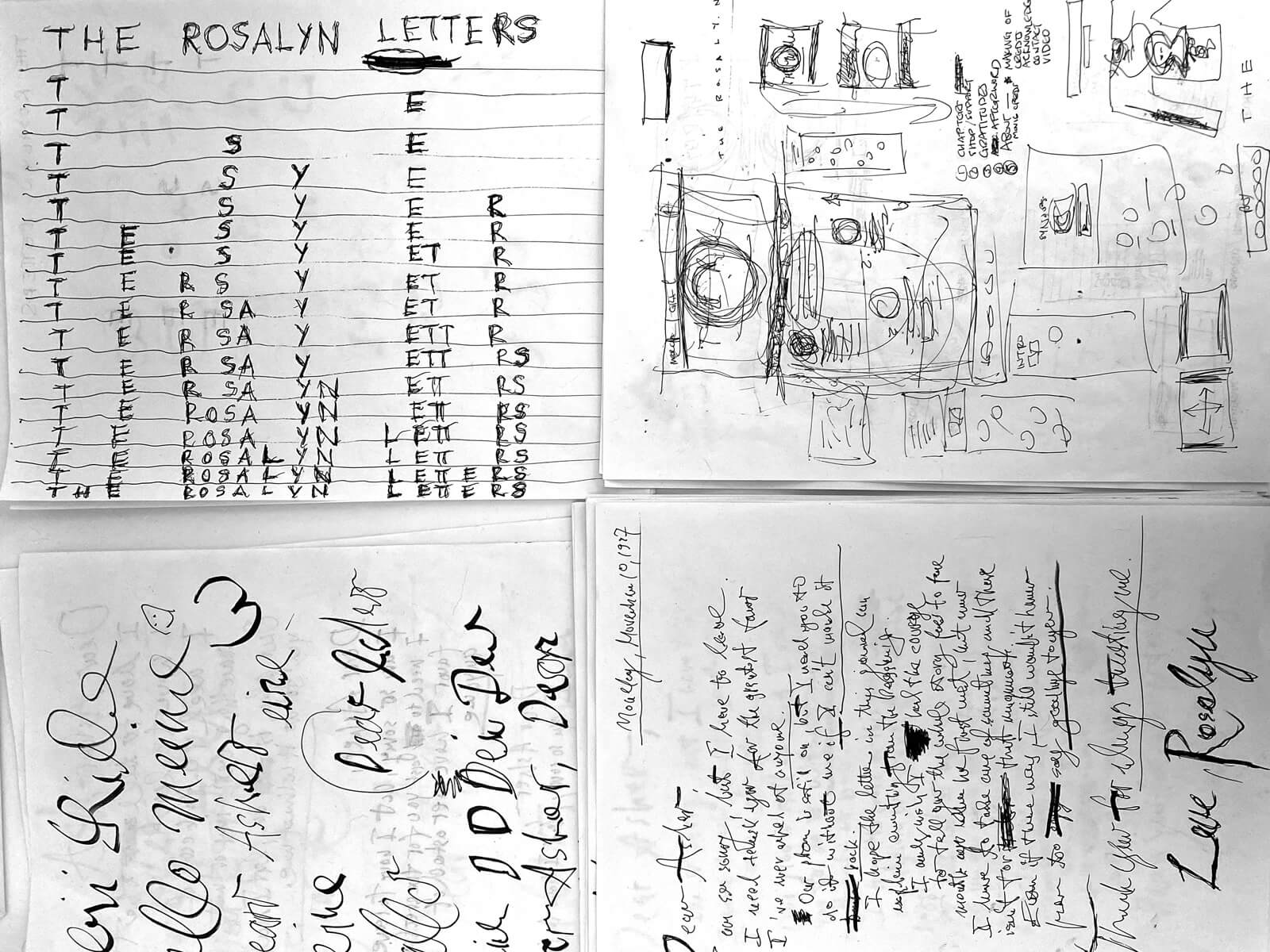

For the first few years, I still wasn’t even remotely sure what I was making. I only promised myself to keep searching, guided by nothing more than an instinct for the storyline’s basic framework and key ingredients. I knew I wanted the project to include a combination of epistolary prose, narrative poetry, and visual art—all through the protagonist’s perspective—though their balance and arrangements were still a mystery. I even dreamed of eventually extending it into an auditory or film experience. The medium felt inextricably married to the story itself, making it easy to get stuck and bogged down in the limitations of my abilities and resources. With my expansive knowledge of eight chords, I bought a guitar to play around and record distorted ambient tones over excerpts from early drafts of the poems. I created a Spotify playlist to convey the project’s mood—Nine Inch Nails, Godspeed You! Black Emperor, and Brian Eno did abound. I made a list of movies that captured the right feeling and art direction. I sketched out characters like they teach you in art school, then like comic book characters, and then like a five-year-old had drawn them. I made animated prototypes. I listened to Mary Oliver read poetry. I watched old black-and-white movies of Picasso painting faces on glass. My mind was goulash, and I wasn’t even sure what I was on the hunt for—maybe just shapes and sounds and gestures that felt like home.

About half a year earlier, I’d started making a more concerted effort to remove myself from “the grind” as much as possible. I reconnected with my love of poetry and performance art. I was reading a new book every few weeks. I was having more honest conversations with my friends about my creative curiosities, vulnerabilities, and process. And though I was still consistently and quietly making personal art, I’d noticed how I seemed to bore easily if my images lacked a storyline or expressed purpose. I spent more time connecting with my body through sports and the outdoors. I’d taken a retreat to Colombia to explore medicine healing and root myself in a more intuitive, nature-based understanding of the universe. I felt more ready to share with others the mysterious storytelling project I’d been working on for two years now in the late hours of nights and weekends. Conceptually, I knew exactly what I wanted to articulate. Executionally, I still had my work cut out. When the first words had demanded their freedom from their entrapment of my skull two years prior, I didn’t know much of anything—only an impulse to obey a few quiet instincts. Strangely, what had emerged was not some omniscient narration or description of a scene but inexplicably several lines of rhyming AABB poetry in the main character’s voice. Somehow I knew her name was Rosalyn.

I began to imagine what a written story might feel like if it was a closer cousin to The Who’s Tommy or David Bowie’s Ziggy Stardust than to a novel, their albums containing full story arcs from start to finish, complete with characters and scenes. Yet alone, each individual song still carries its own narrative and musical power in isolation. Could elements of a book do that too? I wondered what a graphic novel might look like if it was drawn by Miró, Hilma af Klint, or Basquiat instead of Dave Gibbons. And what might it sound like if it were read by Patti Smith? Questions like these made the work ahead exceptionally slow, messy, and circuitous but endlessly fascinating.

For the first few years, I still wasn’t even remotely sure what I was making. I only promised myself to keep searching, guided by nothing more than an instinct for the storyline’s basic framework and key ingredients. I knew I wanted the project to include a combination of epistolary prose, narrative poetry, and visual art—all through the protagonist’s perspective—though their balance and arrangements were still a mystery. I even dreamed of eventually extending it into an auditory or film experience. The medium felt inextricably married to the story itself, making it easy to get stuck and bogged down in the limitations of my abilities and resources. With my expansive knowledge of eight chords, I bought a guitar to play around and record distorted ambient tones over excerpts from early drafts of the poems. I created a Spotify playlist to convey the project’s mood—Nine Inch Nails, Godspeed You! Black Emperor, and Brian Eno did abound. I made a list of movies that captured the right feeling and art direction. I sketched out characters like they teach you in art school, then like comic book characters, and then like a five-year-old had drawn them. I made animated prototypes. I listened to Mary Oliver read poetry. I watched old black-and-white movies of Picasso painting faces on glass. My mind was goulash, and I wasn’t even sure what I was on the hunt for—maybe just shapes and sounds and gestures that felt like home.

2017-2021

Style explorations and thumbnails over the years for the first chapter (dead moon)

Style explorations and thumbnails over the years for the first chapter (dead moon)

2017

discarded character sketch from early draft

discarded character sketch from early draft

2018

abandoned sketch for a character who was eventually cut

abandoned sketch for a character who was eventually cut

2018

a scroll-triggered animation prototype when the draft story was still set in the future

a scroll-triggered animation prototype when the draft story was still set in the future

Cube One

It was a Thursday afternoon in September 2019, and I’d been staring at my outstretched left leg for several hours. I watched it slowly rise and fall in the sling of a machine that rotated it for me like an elliptical machine, only I was horizontal in my bed. The week before, I’d undergone elective surgery to repair cartilage that had torn from the bone in my hip socket, leaving me with a cocktail of hip, back, sacrum, and sciatic pain from what I had assumed must be overuse from sports. (Or, had it just been a love tap from everyone’s least favorite freeloading roommate, Chronic Stress, who had never been invited to stay with us in the first place?)Across the room, a stack of a dozen or so pieces of black, three-foot-tall foamboard leaned against the wall. A few weeks before surgery, I’d duct-taped them together into accordions, allowing them to stand upright on the floor in freestanding panels. The foamboard partitions were my alchemy lab. Instantly, the square footage of my studio apartment multiplied as the new wall space sprung forth across their surfaces. And then, like Cinderella's pumpkin, everything went back to the way it was before when I folded them back up and rested them in the corner.

That year I’d started to make some serious progress. I’d begun to feel less sheepish about the possibility that I might be writing an actual book, and I dedicated myself to its exploration. A shortage of ideas was never the challenge–it was how to sort out their surplus. How would I translate so many swarms of concepts and themes into a coherent story? I was writing consistently every weekend and at night after my job, and eventually, I managed to scrounge together a draft manuscript, complete with cues for the inclusion of accompanying illustrations. By this time, the project was well-defined as a crime thriller from the first-person perspective of Rosalyn’s journal, and the plot thickened when Rosalyn realizes her dreams might somehow be clues to solve the crime. Her dreams were all expressed as poems—a device I employed to break with reality—and I devoted hundreds of hours to the great task of weaving them all together. The sheer complexity of mapping out the mystery was a thrilling challenge. I, the author, knew things that Rosalyn (and the reader) did not, and I had to figure out how to tease the clues slowly and with the right subtleties throughout the manuscript to create the intended suspense.

My solution was to create a physical map. I printed the corresponding passages for each clue and taped them onto the foam board like a detective’s war room. If I changed a detail, I could visually follow its impact on the rest of the story. It was like a horizontal Jenga set made of rhyming couplets instead of blocks. Because each chapter was also formatted as a dated letter, I also needed to ensure my temporal references added up. For this, I created a calendar and appended any other key information, such as full moons or plot developments, that I might need to refer to in descriptions. I had to know how everything related. This seemed to work well, and it was motivating to see the story physically take shape. I knew I had the beginnings of something interesting, but I still had no idea how far away I was from a readable book.

***

The machine’s motor made a whirring sound, and the white noise was strangely calming. I gazed over at the foam board across the room, a constant reminder of my unfinished work. I’d been rendered a hobble-goblin (not to be confused with their much more fun and mischievous cousins, Hobgoblins), and I’d be unable to walk for over a month. I now had some much-needed downtime to reflect and rest. The post-op meds had given me substantial brain fog—creatively, I was useless. But perhaps I could still make progress in other ways. I knew I had a solid foundation of a structure and a process, but I was too deep in my head, and I was getting carried away. My instincts bristled. Something was bothering me. As with any project, there comes a time when it’s necessary to pause and check in—both with yourself and others—and as I found myself recovering, this felt like a natural intermission.

I asked a close friend if he’d be willing to give my latest a read for some feedback. Generously, he acquiesced. I respected his opinion immensely, and he’d already published a book of his own. I knew he empathized with the challenges and process. Even if he thought my story was total gunk, at least he might be tender to the significant difficulties of even making so-much-as-gunk. My heart fluttered as I typed my proposal.“Hello, my friend! Thank you so much for your support and for offering to be one of the very few early first-draft readers :) I shall forever be in debt and will do my best to repay you with many beer, wine, puppy GIFs, and food gifts. The story is called Rosalyn and is centered around a dark murder mystery set in futuristic dystopian New York and a fictional mystical island nation-state called Nossomnia. Our reluctant hero Rosalyn discovers that over the course of a year (2073), her dreams are delivering the clues to catch a killer. However, as she uncovers more, she learns the crime is much bigger and more dangerous than she ever could have imagined. Will she trust what she knows? The vibe is something of Orwell’s “Nineteen Eighty-Four” meets “Blade Runner” meets Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Raven,” so if you like any of those things, I hope you might enjoy this story.”

I attached my latest draft and hit send. Within only a week, a seventeen-hundred-word reply was waiting for me in my inbox, the content of which was wonderfully thoughtful and thorough. “I wanted to acknowledge you're trying to do four difficult things here, all at the same time. Having someone tell me this when I was writing made me feel better about how hard it was! We’re all ambitious with our first projects. You’re juggling: Writing tight, rhyming, prophetic-sounding verse, writing POV psychologically intensive narrative with journal entries, world-building a new sci-fi culture with alternate history, and heavy intertextuality with books, literary references, and so on.”

He was right. I agreed with every single one of his points, and they echoed instincts I’d been trying to repress and ignore for months. Even as the all-powerful puppeteer of the narrative, I often became confused and overwhelmed. Initially, my choice of a setting fifty years in the future felt freeing. I could invent and imagine anything I wanted. There were no rules. But quickly, I realized I’d have to spend so much of the narrative merely setting up the circumstances of its futurist backdrop instead of focusing on Rosalyn’s inner journey—which I’d known from the outset was always the central mission. I wanted the story to be about Rosalyn’s conversation with herself, her dreams, and their metaphors. The elaborate, futuristic side story only seemed to create noise. Essentially, I had a forty-five-thousand-word outline set in the wrong time, in the wrong place, with the wrong characters, the wrong plot, and the wrong format. Finally, I was getting somewhere. At least knowing where not to go was a nod in the right direction.

The beloved idiom “back to square one” originally came from football radio commentaries in the 1930s. Because they needed a way to describe the plays without visuals to reference, the commentators mentally divided the football pitch into a numbered grid and used the numbers to refer to the position of the plays. “Square one” was in front of the home team's goal, and as the number increased, the areas moved up the pitch. When the home team kicked a goal, the play was described as being back at square one. That’s where I was too. Back at the beginning trying my best to kick a goal. But what were the rules to my game? And what was my new strategy? I suddenly felt like I had so many dimensions to resolve. Setting. Characters Plot. Format. I felt like I was playing on the face of a multi-dimensional polyhedron with too many vertexes to count. If not a square, at least I was back at cube one.

I sent my friend a few bottles of wine and moped around on my crutches for a week or two in a display of resistance to the dizzying job ahead. Then I got back to work.

That year I’d started to make some serious progress. I’d begun to feel less sheepish about the possibility that I might be writing an actual book, and I dedicated myself to its exploration. A shortage of ideas was never the challenge–it was how to sort out their surplus. How would I translate so many swarms of concepts and themes into a coherent story? I was writing consistently every weekend and at night after my job, and eventually, I managed to scrounge together a draft manuscript, complete with cues for the inclusion of accompanying illustrations. By this time, the project was well-defined as a crime thriller from the first-person perspective of Rosalyn’s journal, and the plot thickened when Rosalyn realizes her dreams might somehow be clues to solve the crime. Her dreams were all expressed as poems—a device I employed to break with reality—and I devoted hundreds of hours to the great task of weaving them all together. The sheer complexity of mapping out the mystery was a thrilling challenge. I, the author, knew things that Rosalyn (and the reader) did not, and I had to figure out how to tease the clues slowly and with the right subtleties throughout the manuscript to create the intended suspense.

My solution was to create a physical map. I printed the corresponding passages for each clue and taped them onto the foam board like a detective’s war room. If I changed a detail, I could visually follow its impact on the rest of the story. It was like a horizontal Jenga set made of rhyming couplets instead of blocks. Because each chapter was also formatted as a dated letter, I also needed to ensure my temporal references added up. For this, I created a calendar and appended any other key information, such as full moons or plot developments, that I might need to refer to in descriptions. I had to know how everything related. This seemed to work well, and it was motivating to see the story physically take shape. I knew I had the beginnings of something interesting, but I still had no idea how far away I was from a readable book.

***

The machine’s motor made a whirring sound, and the white noise was strangely calming. I gazed over at the foam board across the room, a constant reminder of my unfinished work. I’d been rendered a hobble-goblin (not to be confused with their much more fun and mischievous cousins, Hobgoblins), and I’d be unable to walk for over a month. I now had some much-needed downtime to reflect and rest. The post-op meds had given me substantial brain fog—creatively, I was useless. But perhaps I could still make progress in other ways. I knew I had a solid foundation of a structure and a process, but I was too deep in my head, and I was getting carried away. My instincts bristled. Something was bothering me. As with any project, there comes a time when it’s necessary to pause and check in—both with yourself and others—and as I found myself recovering, this felt like a natural intermission.

I asked a close friend if he’d be willing to give my latest a read for some feedback. Generously, he acquiesced. I respected his opinion immensely, and he’d already published a book of his own. I knew he empathized with the challenges and process. Even if he thought my story was total gunk, at least he might be tender to the significant difficulties of even making so-much-as-gunk. My heart fluttered as I typed my proposal.“Hello, my friend! Thank you so much for your support and for offering to be one of the very few early first-draft readers :) I shall forever be in debt and will do my best to repay you with many beer, wine, puppy GIFs, and food gifts. The story is called Rosalyn and is centered around a dark murder mystery set in futuristic dystopian New York and a fictional mystical island nation-state called Nossomnia. Our reluctant hero Rosalyn discovers that over the course of a year (2073), her dreams are delivering the clues to catch a killer. However, as she uncovers more, she learns the crime is much bigger and more dangerous than she ever could have imagined. Will she trust what she knows? The vibe is something of Orwell’s “Nineteen Eighty-Four” meets “Blade Runner” meets Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Raven,” so if you like any of those things, I hope you might enjoy this story.”

I attached my latest draft and hit send. Within only a week, a seventeen-hundred-word reply was waiting for me in my inbox, the content of which was wonderfully thoughtful and thorough. “I wanted to acknowledge you're trying to do four difficult things here, all at the same time. Having someone tell me this when I was writing made me feel better about how hard it was! We’re all ambitious with our first projects. You’re juggling: Writing tight, rhyming, prophetic-sounding verse, writing POV psychologically intensive narrative with journal entries, world-building a new sci-fi culture with alternate history, and heavy intertextuality with books, literary references, and so on.”

He was right. I agreed with every single one of his points, and they echoed instincts I’d been trying to repress and ignore for months. Even as the all-powerful puppeteer of the narrative, I often became confused and overwhelmed. Initially, my choice of a setting fifty years in the future felt freeing. I could invent and imagine anything I wanted. There were no rules. But quickly, I realized I’d have to spend so much of the narrative merely setting up the circumstances of its futurist backdrop instead of focusing on Rosalyn’s inner journey—which I’d known from the outset was always the central mission. I wanted the story to be about Rosalyn’s conversation with herself, her dreams, and their metaphors. The elaborate, futuristic side story only seemed to create noise. Essentially, I had a forty-five-thousand-word outline set in the wrong time, in the wrong place, with the wrong characters, the wrong plot, and the wrong format. Finally, I was getting somewhere. At least knowing where not to go was a nod in the right direction.

The beloved idiom “back to square one” originally came from football radio commentaries in the 1930s. Because they needed a way to describe the plays without visuals to reference, the commentators mentally divided the football pitch into a numbered grid and used the numbers to refer to the position of the plays. “Square one” was in front of the home team's goal, and as the number increased, the areas moved up the pitch. When the home team kicked a goal, the play was described as being back at square one. That’s where I was too. Back at the beginning trying my best to kick a goal. But what were the rules to my game? And what was my new strategy? I suddenly felt like I had so many dimensions to resolve. Setting. Characters Plot. Format. I felt like I was playing on the face of a multi-dimensional polyhedron with too many vertexes to count. If not a square, at least I was back at cube one.

I sent my friend a few bottles of wine and moped around on my crutches for a week or two in a display of resistance to the dizzying job ahead. Then I got back to work.

2019

mapping out the clues with the outline

mapping out the clues with the outline

2022

Editing notes with a printed calendar for plot tracking

Editing notes with a printed calendar for plot tracking

Finding Bigfoot

It was March of 2020, and we all know what happened next. Concentration was fragile and frayed, focus as elusive (and potentially mythical) as Bigfoot. A critical reckoning was upon us in more ways than one. I had recently embarked on my quest for coherency as I rethought the key components of my Rosalyn project, and the topic of setting felt more critical than ever. As present day was shaping up to look more and more apocalyptic, I asked myself if any of us really needed another fictional Doomsday. And how much time in my own imagination could I tolerate creating one—especially now?

With my friend’s reinforcing counsel several months earlier, I knew I had to do something I’d been afraid of: scrap the setting and side story altogether. If the surrounding plot didn’t serve the core story, it was time to go. I needed to simplify in a big way and embrace the philosophy that limitations are our friends, their boundaries easing our decisions to highlight only what’s important. A chef’s creation, spotlighted by the backdrop of its clean white plate. Empty, echoing museum corridors meant only to emphasize the art inside.After some head-scratching, eventually, I settled on going backward instead of forwards. 1997 seemed like an uneventful enough year to hide inside. It was still close enough to be nostalgic for many of us, and it was one of the last decades when adolescence still seemed to belong to the locus of one’s specific upbringing—not globalization’s. The 90s were still mostly untainted by the chaos and distraction of digital social structures, and generally speaking, it was maybe one of the last pre-Internet eras when the apocalypse simply felt like a standard account of young adulthood according to normal hormonal flows. It was a simpler time when searching for your identity was something you embarked on in relative introspective isolation alongside only the cast of characters from whatever town, school, or family you happened to find yourself in. Besides, the 90s were my own coming-of-age years, and I had a wellspring of material to pull from. Smashing Pumpkins? Nirvana. Doc Martens? High-fructose corn syrup? Sign me up.

The opportunity for reflection during my injury had turned out to be a gift—a moment of pause to explore new ideas and reinvigorate my conviction in the story’s mission. When 2020 hit, that reflective moment only sprawled into a seemingly unending collective one, all of us hunkered down with our thoughts in a much-needed time-out as we contended with our values. I poured myself into the rewrite, scrapping anything except for the main threads of the crime mystery and the deeper themes of the story’s main symbolic messages. And the more I wrote, the more I realized I was simply writing a story I needed to hear myself more than ever. I hoped others might feel that way too.

By mid-2021, I had another draft in hand and my retired mom, in a characteristic gesture of her unwavering support for my creative endeavors, offered to unofficially become my editor. I made a list of questions that might be helpful to consider while reading, and she quickly jumped in with questions, suggestions, and corrections. With every new draft, she was my objective eye, and it felt reassuring to have someone else on my team who understood what I was striving for, even if we both knew I still had a lot of work to do. The dull drain of the ongoing pandemic was taking its toll, but I was just thankful for the health of myself and my loved ones—as well as for the physical separation it afforded me from my mounting personal and professional responsibilities. Nerves were thinner than ever, but I would have to find Bigfoot if I was ever going to get this thing finished.

With my friend’s reinforcing counsel several months earlier, I knew I had to do something I’d been afraid of: scrap the setting and side story altogether. If the surrounding plot didn’t serve the core story, it was time to go. I needed to simplify in a big way and embrace the philosophy that limitations are our friends, their boundaries easing our decisions to highlight only what’s important. A chef’s creation, spotlighted by the backdrop of its clean white plate. Empty, echoing museum corridors meant only to emphasize the art inside.After some head-scratching, eventually, I settled on going backward instead of forwards. 1997 seemed like an uneventful enough year to hide inside. It was still close enough to be nostalgic for many of us, and it was one of the last decades when adolescence still seemed to belong to the locus of one’s specific upbringing—not globalization’s. The 90s were still mostly untainted by the chaos and distraction of digital social structures, and generally speaking, it was maybe one of the last pre-Internet eras when the apocalypse simply felt like a standard account of young adulthood according to normal hormonal flows. It was a simpler time when searching for your identity was something you embarked on in relative introspective isolation alongside only the cast of characters from whatever town, school, or family you happened to find yourself in. Besides, the 90s were my own coming-of-age years, and I had a wellspring of material to pull from. Smashing Pumpkins? Nirvana. Doc Martens? High-fructose corn syrup? Sign me up.

The opportunity for reflection during my injury had turned out to be a gift—a moment of pause to explore new ideas and reinvigorate my conviction in the story’s mission. When 2020 hit, that reflective moment only sprawled into a seemingly unending collective one, all of us hunkered down with our thoughts in a much-needed time-out as we contended with our values. I poured myself into the rewrite, scrapping anything except for the main threads of the crime mystery and the deeper themes of the story’s main symbolic messages. And the more I wrote, the more I realized I was simply writing a story I needed to hear myself more than ever. I hoped others might feel that way too.

By mid-2021, I had another draft in hand and my retired mom, in a characteristic gesture of her unwavering support for my creative endeavors, offered to unofficially become my editor. I made a list of questions that might be helpful to consider while reading, and she quickly jumped in with questions, suggestions, and corrections. With every new draft, she was my objective eye, and it felt reassuring to have someone else on my team who understood what I was striving for, even if we both knew I still had a lot of work to do. The dull drain of the ongoing pandemic was taking its toll, but I was just thankful for the health of myself and my loved ones—as well as for the physical separation it afforded me from my mounting personal and professional responsibilities. Nerves were thinner than ever, but I would have to find Bigfoot if I was ever going to get this thing finished.

Thanks Georgia

By the beginning of 2022, I was feeling closer and more confident. I’d even started openly referring to it as a “book” amongst friends rather than just a meek “side project,” but it was still a plodding extracurricular undertaking. I was more spread thin than ever, and as I ironed out the book’s wrinkles, they seemed to miraculously relocate to the corners of my eyes. If I was ever going to make something I was really proud of, I knew I’d still have to push much harder. Something had to give, and I’d already been operating well beyond my limits for months, if not years. When the green camera light went off after back-to-back Zoom meetings, and I opened myself a numbing beer or three, I thought more and more about those first days in November of 2016 when I’d started writing. What was it that had made me pick up my pen? Then I thought back even further, all the way back to my very first days in New York City, still so bright-eyed with all my dreams of becoming an artist one day.

Just before the pandemic had hit, I’d taken a personal day on a Monday to visit with an old friend in Brooklyn who was a talented artist. We’d met in advertising years before, and we reminisced about our early days working at an agency and wistfully described the flames of our art side hustles we each still fanned. When we’d finished our coffees, I headed to The Brooklyn Museum to wander around alone and feel the art. I can’t even remember the exhibition. I just remember somehow feeling sad and afraid. On my way out, I bought a book about Georgia O’Keeffe that was on sale in the gift shop and then rode the train back toward my apartment in the Village in a melancholic haze.

When I got home, I placed Georgia’s book in constant view so its cover would inspire me, but I barely flipped through. Maybe I didn’t actually want to feel inspired—at least not yet. It was all too frightening. It wasn’t until the evening of January 1, 2022 two years later, that I finally slid Georgia’s book back out. I stretched myself out on the floor with it and read details of her biography that I’d never known before. Early in her career, Georgia had landed a job as an art teacher. In many ways, that alone established her as a success story, supporting herself with a paying job in her chosen field—especially as a woman at the time. But the following year, she quit and moved to New York, gambling everything for love—both for the photographer and gallerist Alfred Stieglitz and for the prospect of blossoming her personal art career. The choice was a massive risk, but to Georgia, a worthy one. Her art wasn’t just about the marks of her brush. It was about one’s way of living.With tears in my eyes, I pushed the book aside. My mind was made up. By that April, with the encouragement of my partner, family, and even my colleagues, I quit my job and sold everything I owned in New York. Just like Georgia, art brought me to this city. But also like Georgia, now I was leaving it too. In the summer of 1929, Georgia visited New Mexico, and its influence changed the direction of her art forever. It's the seminal work she’s known for today, and in 1949 she finally moved there permanently. “You win for now, New York,” I thought to myself. “I’ll get my coffee somewhere else.” And for the remainder of 2022, I edited full-time in the woods.

Just before the pandemic had hit, I’d taken a personal day on a Monday to visit with an old friend in Brooklyn who was a talented artist. We’d met in advertising years before, and we reminisced about our early days working at an agency and wistfully described the flames of our art side hustles we each still fanned. When we’d finished our coffees, I headed to The Brooklyn Museum to wander around alone and feel the art. I can’t even remember the exhibition. I just remember somehow feeling sad and afraid. On my way out, I bought a book about Georgia O’Keeffe that was on sale in the gift shop and then rode the train back toward my apartment in the Village in a melancholic haze.

When I got home, I placed Georgia’s book in constant view so its cover would inspire me, but I barely flipped through. Maybe I didn’t actually want to feel inspired—at least not yet. It was all too frightening. It wasn’t until the evening of January 1, 2022 two years later, that I finally slid Georgia’s book back out. I stretched myself out on the floor with it and read details of her biography that I’d never known before. Early in her career, Georgia had landed a job as an art teacher. In many ways, that alone established her as a success story, supporting herself with a paying job in her chosen field—especially as a woman at the time. But the following year, she quit and moved to New York, gambling everything for love—both for the photographer and gallerist Alfred Stieglitz and for the prospect of blossoming her personal art career. The choice was a massive risk, but to Georgia, a worthy one. Her art wasn’t just about the marks of her brush. It was about one’s way of living.With tears in my eyes, I pushed the book aside. My mind was made up. By that April, with the encouragement of my partner, family, and even my colleagues, I quit my job and sold everything I owned in New York. Just like Georgia, art brought me to this city. But also like Georgia, now I was leaving it too. In the summer of 1929, Georgia visited New Mexico, and its influence changed the direction of her art forever. It's the seminal work she’s known for today, and in 1949 she finally moved there permanently. “You win for now, New York,” I thought to myself. “I’ll get my coffee somewhere else.” And for the remainder of 2022, I edited full-time in the woods.

The Very Point

I’d just finished another edit. It was the fourth or fifth round after already declaring I was on the final read. “Keep pushing,” my partner told me. “You just have to spend the time—time shows.” I spent countless hours researching strange topics I never thought I’d be googling. I interviewed friends and family who were experts in subjects mentioned in the book. I even re-wrote the last hundred pages after a discussion with a family member who again reinforced a not-insignificant concern I, too, had been harboring. My early lessons in rewrites had primed me well. In the beginning, each word required so much focus and energy to just get down on paper, and it could be acerbically painstaking to accept the need to change so much as a single rhyme in a stanza. But by the final months, I’d learned to cut out or rework years of work within seconds, so long as I was sure the delete button improved what I’d set out to create in the first place.

This was also true for the artwork. Though I'd been sketching and experimenting since the early days, the final art direction didn't coalesce until the last few rounds of editing. As a remnant of some of the early concepts, I’d imagined the book as a record, and I wanted not only the album to have its own art but each song too. I dreamed of wearing an old, worn-in t-shirt that looked like it could be for one of my favorite underground bands—only it was for a novel instead. It felt punk rock, but it also spoke to why I’d always wanted to make art in the first place. We garb ourselves in the memorabilia of the musicians we love because their sounds dredge forth something buried inside us that we want to put on display. But what could be cool enough to warrant a t-shirt for a book, I pondered. This would take some time. It wasn’t until sometime in December 2021 that I felt like I'd finally cracked the answer—a naive, stripped down, childlike direction á la Daniel Johnston’s “Hi, How Are You,” and I’d only come by accidentally while doodling. I’d made a quick thumbnail sketch but quickly decided I liked it much better than the more rendered final version it was supposed to inform. I was close, but to get each final drawing right required many dozens of replications. I drew hundreds of versions of each of the seventeen chapters and made them into little frame animations for the book’s website, giving them a spooky aliveness onscreen. I even made those band t-shirts I’d dreamed of.

As for the book’s cover art, I’d hoped to check that off the list early. Back in 2019, long before the manuscript was finished, I’d recreated a physical, hand-embroidered version of Rosalyn’s journal on black linen. The design included her name in whimsical white letters, wrapped around a moon and a wide eye. It was integral to the story, and even three years later, when I was finally gearing up to publish, I was sure it was the only possible subject for the cover. Preferring the creative control and experimentation of self-publishing (and the convenient insulation from rejection), I ordered my own printed proofs from various suppliers as I entered the final rounds of proofreading. I experimented with software, formatting, and materials, and I eagerly awaited my deliveries. When they arrived weeks later, I opened the box with equal parts glee and disappointment. The color fidelity of the cover wasn’t reading well on the laminate, and I wouldn’t always have control over consistency. I was again faced with another square-one-moment. I knew right away I had to think of a new and cleaner design—and quickly, too, if I was going to stay on schedule for printing before the end of the year.That same week, Editor Mom was already scheduled to arrive at my woodland escape for a mother-daughter visit. We cooked and re-acclimated to our still infrequent in-person hangouts since the pandemic. She proofread on the couch while I sketched and messed around in Photoshop. Three days passed in a medium-sized tizzy as I searched for a solution. In rapid fire succession, I went through nearly forty black-and-white designs until an accidental test rendered a delightful surprise. It had been cobbled together from several old sketches, but immediately, I loved its simplicity—a deconstructed sketched version of the original embroidery, still a nod to the concept, but more gestural and emotive. It followed the same art direction as the other sketched chapter illustrations. At last, it was all making sense, and I loved its minimalism. The setback had again turned out to be fortuitous.

That Saturday before my mom embarked on her trip back home, she, I, and my partner lounged in the living room in our sweatpants with snacks. We passed around one of the printed proofs, the new cover design taped over the front. We all chirped with suggestions for tweaks. As the sun grew low, my partner and I played around with the website on one end of the couch while my mom snuggled into the other, quietly proofreading for the umpteenth time, post-its peaking from the nearly three hundred pages she’d already devoured since arriving. It was all hands on deck. I stood up to use the restroom, and as I looked over my shoulder, I felt my throat close in a rush of emotion. Here were my loved ones spending their Saturdays supporting my dream. I wondered what I’d done in life to be so lucky. Surely these must be the shapes and sounds and gestures that felt like home I’d been searching for all those years ago. And surely, they’ll be the ones I remember years from now.

Any creative undertaking is chaotic, winding, and often equally as joyous as it is painful and scary. We never get assurances that our toil will be all for nothing—that is, unless we subscribe to the belief that the toil itself is enough—if not the very point. There will be too many discarded ideas, words, and designs to count—too many to even recall by the end. And certainly, there are never any how-to guides or step-by-step tutorials to follow, no matter how many you may find on the Internet. And that’s how it should be. That’s the process we all sign up for when we undertake the pursuit of any craft. And as with any creative undertaking or important choice in life, we’re never ensured its outcome. Even as we know what we must do next, the future ahead will be murky and most uncertain.

This was also true for the artwork. Though I'd been sketching and experimenting since the early days, the final art direction didn't coalesce until the last few rounds of editing. As a remnant of some of the early concepts, I’d imagined the book as a record, and I wanted not only the album to have its own art but each song too. I dreamed of wearing an old, worn-in t-shirt that looked like it could be for one of my favorite underground bands—only it was for a novel instead. It felt punk rock, but it also spoke to why I’d always wanted to make art in the first place. We garb ourselves in the memorabilia of the musicians we love because their sounds dredge forth something buried inside us that we want to put on display. But what could be cool enough to warrant a t-shirt for a book, I pondered. This would take some time. It wasn’t until sometime in December 2021 that I felt like I'd finally cracked the answer—a naive, stripped down, childlike direction á la Daniel Johnston’s “Hi, How Are You,” and I’d only come by accidentally while doodling. I’d made a quick thumbnail sketch but quickly decided I liked it much better than the more rendered final version it was supposed to inform. I was close, but to get each final drawing right required many dozens of replications. I drew hundreds of versions of each of the seventeen chapters and made them into little frame animations for the book’s website, giving them a spooky aliveness onscreen. I even made those band t-shirts I’d dreamed of.

As for the book’s cover art, I’d hoped to check that off the list early. Back in 2019, long before the manuscript was finished, I’d recreated a physical, hand-embroidered version of Rosalyn’s journal on black linen. The design included her name in whimsical white letters, wrapped around a moon and a wide eye. It was integral to the story, and even three years later, when I was finally gearing up to publish, I was sure it was the only possible subject for the cover. Preferring the creative control and experimentation of self-publishing (and the convenient insulation from rejection), I ordered my own printed proofs from various suppliers as I entered the final rounds of proofreading. I experimented with software, formatting, and materials, and I eagerly awaited my deliveries. When they arrived weeks later, I opened the box with equal parts glee and disappointment. The color fidelity of the cover wasn’t reading well on the laminate, and I wouldn’t always have control over consistency. I was again faced with another square-one-moment. I knew right away I had to think of a new and cleaner design—and quickly, too, if I was going to stay on schedule for printing before the end of the year.That same week, Editor Mom was already scheduled to arrive at my woodland escape for a mother-daughter visit. We cooked and re-acclimated to our still infrequent in-person hangouts since the pandemic. She proofread on the couch while I sketched and messed around in Photoshop. Three days passed in a medium-sized tizzy as I searched for a solution. In rapid fire succession, I went through nearly forty black-and-white designs until an accidental test rendered a delightful surprise. It had been cobbled together from several old sketches, but immediately, I loved its simplicity—a deconstructed sketched version of the original embroidery, still a nod to the concept, but more gestural and emotive. It followed the same art direction as the other sketched chapter illustrations. At last, it was all making sense, and I loved its minimalism. The setback had again turned out to be fortuitous.

That Saturday before my mom embarked on her trip back home, she, I, and my partner lounged in the living room in our sweatpants with snacks. We passed around one of the printed proofs, the new cover design taped over the front. We all chirped with suggestions for tweaks. As the sun grew low, my partner and I played around with the website on one end of the couch while my mom snuggled into the other, quietly proofreading for the umpteenth time, post-its peaking from the nearly three hundred pages she’d already devoured since arriving. It was all hands on deck. I stood up to use the restroom, and as I looked over my shoulder, I felt my throat close in a rush of emotion. Here were my loved ones spending their Saturdays supporting my dream. I wondered what I’d done in life to be so lucky. Surely these must be the shapes and sounds and gestures that felt like home I’d been searching for all those years ago. And surely, they’ll be the ones I remember years from now.

Any creative undertaking is chaotic, winding, and often equally as joyous as it is painful and scary. We never get assurances that our toil will be all for nothing—that is, unless we subscribe to the belief that the toil itself is enough—if not the very point. There will be too many discarded ideas, words, and designs to count—too many to even recall by the end. And certainly, there are never any how-to guides or step-by-step tutorials to follow, no matter how many you may find on the Internet. And that’s how it should be. That’s the process we all sign up for when we undertake the pursuit of any craft. And as with any creative undertaking or important choice in life, we’re never ensured its outcome. Even as we know what we must do next, the future ahead will be murky and most uncertain.

2021

Drawing pieces for The Door with the Face chapter key art

Drawing pieces for The Door with the Face chapter key art

2021

hand sewn embroidery created for the original cover design, later changed

hand sewn embroidery created for the original cover design, later changed

2021

VARIOUS SKETCHES AND NOTES FOR KEY ART

VARIOUS SKETCHES AND NOTES FOR KEY ART

2022

Production timeline for publishing and wireframes for website

Production timeline for publishing and wireframes for website

2021

Various sketches for the website design

Various sketches for the website design

2022

A WORKING Dinner time

A WORKING Dinner time

2022

Late night designing and website building at the kitchen table

Late night designing and website building at the kitchen table